Re-Assessing the Origins of Life: Art, Creativity, and Life

In the course of human civilization, the ability to fire clay into ceramic marked the beginning of the Neolithic era. Humans have been discovering and exploring the material properties of clay for more than ten thousand years, and China opened a new frontier in the making of clay into porcelain. In English, “china,” as a term for porcelain, comes from the name of the country, and Kaolin clay is named for Gaoling, China, where it is produced. These terms offer a glimpse into the brilliant history of the porcelain that Chinese people invented and its profound influence on world civilizations.

In explaining the impetus behind “From Clay to Words: Ceramics as Media,” Pearl Art Museum director and curator Li Dandan said, “Ceramic is one of the most ancient and ordinary materials. It is one of the artistic mediums that has the closest connections to China’s history and culture, to the exchange between China and the rest of the world, and to nature. These artists have observed and studied ceramics—they are focused on the history, technique, and tradition of ceramics. The physical properties, firing processes, and cultural attributes unique to ceramics can inspire endless creativity. The process of moving ‘from clay to words’ involves hands, hearts, and fire… These ceramic works are products of nature, of ideas, and of labor. In a sense, they are the products of nature and chance; they are physical objects, but they are also metaphors for and symbols of art, creativity, and life.”

An exhibition view of Pearl Art Museum’s “From Clay to Words: Ceramics as Media” with Sui Jianguo’s Clay Draft of Boxing

An Inspired Tour in Seven Parts, An Endless Vision in Ceramic

The exhibition showcases more than thirty works in ceramic or related to ceramics made by fourteen artists from around the world. The seven sections—“Born Out of Earth,” “Studying the Nature of Things,” “Nostalgia and Appropriation,” “Ordinary and Extraordinary,” “Body and Identity,” “Time,” and “Synesthesia and Nature”—urge the viewer to look at the works from different perspectives, to open space for imagination, and to appreciate the artists’ creative ideas. Because of the diversity and richness of their work, pieces by certain artists appear in several sections, and one work can touch on multiple themes. These thirty works are presented in seven sections in an inspiring and relaxed way, blurring the boundaries between them. We hope that visitors will wander among them, as they spark new ideas.

Sui Jianguo’s video work Physical Trace at Pearl Art Museum’s “From Clay to Words: Ceramics as Media”

Zhuangzi: Letting Be, and Exercising Forbearance states, “At present all things are produced from the Earth and return to the Earth.” The exhibition opens with the idea that the earth was the starting point for all things, which helps visitors to explore the origins of art and life. As Sui Jianguo has said, “People have worked with clay for ten thousand years … Pinching and kneading, humans create the world.” His video work Physical Trace records him punching clay, in a work that is a continuation of his Portrait of a Blind Manseries (2008). He shuts down his visual senses and attempts to shake off the language and thinking of traditional sculpture. He places bodily movement at the core of the work, returning clay sculpture back to its original state and pushing the sense of touch, or humanity’s sensation of the soul, to its utmost point. Clay Draft of Boxing, exhibited together with the video, is the physical object that resulted from the video.

Another work in the “Born Out of Earth” section is Geng Xue’s clay stop-motion animation The Name of Gold. Taking clay as a symbol of life, the clay figures in Geng’s video make their way through a black and white world, working in shifts to create a massive object that contains a golden realm. They sacrifice for one another, and their journey from intact to broken shows the trauma, suffering, and creativity in human history, reflecting life and existence for people in the real world. The installations paired with the animation are scattered in front of the screen. These large golden bowls are inlaid with smaller screens, playing videos of those golden figures on a loop. When viewers look down, they seem to be peering into a well to glimpse the spring of life; the magic of the experience intensifies the sense of fate.

The Classic of Rites: The Great Learning states, “Such extension of knowledge lay in the investigation of things. Things being investigated, knowledge became complete.” This section of the exhibition shows more of the ways that artists have investigated and explored the material and presented their refined and innovative expression of traditional ceramic styles. Occasionally, a viewer will exclaim, “So that’s how ceramics are made!” For example, in the work Line at the museum’s entrance, Liu Jianhua usesceladon to create simple lines, subverting past visual experiences of the material and offering a new understanding of ceramics and of line.

Color, another of Liu Jianhua’s works, retains the initial state of hand-kneaded clay. The diversity of color is embodied in pure and simple lumps of clay. Splits in the clay that occur in the firing process are presented naturally. Here, purity shapes the spirit.

Square, located in a small, dark room, brings together ceramics and the industrial texture of steel, transforming the ceramic into golden pools of “liquid” that seem to have fallen from the sky, “distilled” onto square steel plates. As a material also tempered by fire, steel is hard but rusts easily, while ceramic is fragile but can also be preserved for long periods. The antagonism and dependence of the collision of square and round shapes and the juxtaposition of materials are presented as pure form. For Liu Jianhua, “Purity is the essence of the work; it also stems from someone’s own understanding of and response to a material.”

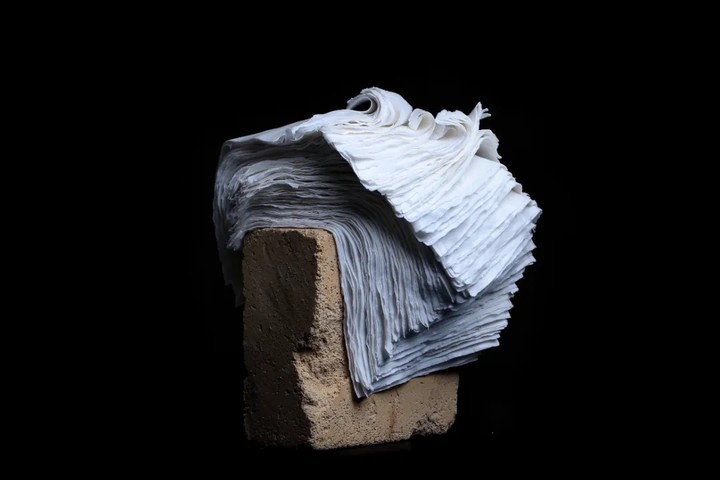

In the “Studying the Nature of Things” section, there are several works that viewers would not believe are made of ceramic. Su Xianzhong, who comes from a long line of Dehua Blanc de Chine makers, imbues the hardness of porcelain with the softness of paper. The layers of white porcelain “paper,” each thin as a cicada’s wing, showcase the Dehua technique of eggshell porcelain sculpture, while also offering a contemporary expression of Buddhist thought. He has breathed new life into porcelain, an ancient material, bringing out its poetic side. The brick-shaped base comes from the kiln that fired the porcelain paper. The ceramic and porcelain, the rough and smooth are contrasting elements, but they are also mutually engendering and interdependent. A piece from Su’s Paper series is part of the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Liu Danhua’s Ash at Pearl Art Museum’s “From Clay to Words: Ceramics as Media”

Across from Su Xianzhong’s Paper is another work entitled Ash. This lifelike ceramic representation of a piece of paper that is about to burn up and turn completely to ash was made by Liu Danhua, who also comes from a family of porcelain makers and has been familiar with ceramic techniques since childhood. He challenges the limitations of the medium, using traditional sculpting methods and hand-applied glazes to achieve a refined, subtle visual effect on super-thin eggshell porcelain. For Liu Danhua, “When paper is burnt, it becomes ash, and when clay is fired, it becomes ash to a certain extent; it’s just that we call this ash ‘porcelain.’” For the exhibition, a red light has been placed behind Ash, highlighting this unique work that looks as if it is about to burn and be reborn from the ashes.

Nostalgia and appropriation are common working methods or themes in post-modern art. The Xu Zhen® contribution to this exhibition is MadeIn Curved Vase – Famille Rose Olive Vase with Bat and Peach Design, Yongzheng Period, Qing Dynasty. The original model for the piece was a legendary famille rose vase that was once used as a table lamp, then broke sales records for Qing dynasty porcelain vases, and entered a museum collection. Using the firing methods of ancient porcelains, Xu Zhen® bends the neck of a classic Chinese porcelain vase ninety degrees, creating a new shape.

Zhao Zhao’s World (left, right), Constellations (center), and a Song dynasty Jian ware black-glazed bowl with hare’s fur decoration and a bronze rim from his collection at Pearl Art Museum’s “From Clay to Words: Ceramics as Media”

Zhao Zhao’s three contemporary paintings are juxtaposed with a Song dynasty Jian ware black-glazed bowl with hare’s fur decoration and a bronze rim from his collection, creating a complete little world. Zhao Zhao’s interests in ancient art and the study of Jian ware bowls are placed into dialogue with his contemporary artworks: “seek impact, seek refinement.” The world seems to be visible in the texture of the glaze in the Jian ware bowl, reflecting World and Constellations. Zhao Zhao does not simply meditate on the past; he activates tradition.

Liu Xi’s work 2020 is both ordinary and extraordinary. She made this piece for the unique year of 2020, but it is also an exploration of the language of materials. In 2020, Liu appropriates the traditional shapes of porcelain vessels, then cuts, distorts, and reorganizes them to create new shapes. They become containers of our current emotions, anxious yet full of hope. Liu combines ceramics and other materials, affixing plastic lichen to the wrinkled, contorted vessels to create something ordinary yet tense with distortion. Green is a lively color, and the arrangement of the pieces from pale green to dark green denotes the passage of time. With time, hope encourages greater comprehension and wisdom. Under the vessels in gradations of green, the top of the oval platform is painted a clear celadon color, while the side is painted a pale pink, akin to the color of clay in a riverbed, thereby suggesting the productive connection from clay to ceramic.

In the “Ordinary and Extraordinary” section, Liang Shaoji’s Drunkness represents his reflections on the unusual circumstances of the 2020 pandemic. Liang employs mixed media, incorporating the natural silk he often uses to represent the circle of life, the pyramidal and spherical flasks that symbolize industrial technology, and the ceramic vessels that signify a lifestyle that is closer to nature. The natural silk spreads like white clouds on the aluminum composite panels, twining around the vessels. It ripples and shimmers in the light, trembling like living breath. Entitled Drunkness, red distiller’s grains were carefully placed inside the flasks. The smell of alcohol is still present, expanding the sensory experience of the work. Liang Shaoji said, “Spherical chemistry glass and smoked ceramic meet amidst the strong spirits, reflecting humanity’s current fascinations and the Earth’s ecological crises.” Bringing the sense of smell into a visual artwork, in a way, connects this work to pieces in “Synesthesia and Nature,” the seventh section.

Liang Wanying’s new work Transplant at first appears to present plants growing in a foreign environment, but the work is actually about human migration and the feeling of entering an unfamiliar culture. She engages with both longer migrations across nations and cultures and shorter journeys between the city and countryside, which are ordinary today yet could also be considered extraordinary. As a Chinese living in North America, Liang transforms her personal experience into creative inspiration. In her view, “This uncertainty is uncomfortable, but it also contains possibilities we can’t imagine.” Her memories of certain life stages and different geographical spaces are dyed with different colors, such as the blue we see here.

Although Xu Xinhua’s Life Museum appears in the “Ordinary and Extraordinary” section, it is located near “Nostalgia and Appropriation.” Because the piece combines ceramics and video, a joint space allows viewers to compare the two. This work is the artist’s everyday life reflected in clay. Working in units of one year, Xu dips daily kitchen scraps (produce and meat) in a porcelain slurry, then records changes in the food with a camera. Finally, he fires the tablets in a high-temperature kiln to turn them into porcelain. At 1,330 degrees, the food evaporates or sublimates, while the porcelain retains the form and color of the original object.

Earth produces all things; clay sculpture and ceramics also nurture people. The majority of the works in this section are connected to people’s bodies and their perceptions of their own identities. For example, another of Xu Xinhua’s works, Body Monument: Device, was created together with his wife, Zhang Chun. Each used black clay to make molds of the other’s body and fired them. They then broke the fired pieces and scattered the fragments on the floor, like flower petals or vessels. These bodily “vessels” contain cow’s milk, a symbol of life. In re-thinking the relationship between bodies and spaces, Xu explores yin and yang, or the sexes. Xu Xinhua said, “The body, the clay, and the world have an isomorphic relationship. The clay becomes an extension of our bodies.”

Chen Xiaodan’s Bloom: Line Series 2007 No. 11 lies between “Body and Identity” and “Synesthesia and Nature.” Large white peonies bloom in a series of wooden boxes arranged in a line. The peonies are made of Jingdezhen high white (gaobai) porcelain, which is hand-sculpted and fired at 1,300 degrees. The flower petals are extremely thin, beautiful, and fragile. The connection between flowers and women’s identities is further intensified by the red mineral pigment scattered among the flower petals. The gorgeous red has instinctive associations with fire and blood. For Chen Xiaodan, this work does not need to be explained with more texts or words. She hopes to communicate with viewers through intuitive visual sensations that resonate on a vital level. She says, “Regardless of the circumstances, life instinctively and tenaciously seeks to survive.”

MAMA, another of Liu Xi’s works presented in the “Body and Identity” section, is comprised of thirty-eight white ceramic washboards of different sizes and shapes. She was inspired by the old washboard that her mother once used; a mother’s unconditional love and sacrifice are reflected in the worn washboards, marked by the passage of time. These sacrificing mothers are admirable and tough, but their bodies are becoming frail and aged, just like the ceramic. Liu Xi spent five years collecting old washboards from around the country to use as models for her ceramic versions that express a mother’s love. The textures worn by time, the wood or bamboo grain patterns, and the carvings characteristic of an era or region are all presented in Liu’s work.

Liang Wanying’s Woman as Vessel is also related to motherhood. This work is located in the “Body and Identity” section, but it is also near “Synesthesia and Nature.” The complex and delicate flower-like vessels offer a contemplation of a mother’s identity and a woman’s body, but they also remind the artist to cherish overlooked everyday moments. Liang has just become a mother, and different experiences and thoughts have arisen from this change in her life. “The obvious sacrifices that mothers make day after day will, after many years, bloom as flowers in their children’s memories. They suddenly realize that their ordinary and unremarkable pasts came by treading on the flowers that contain their mothers’ best wishes. Life is just the desire to transform clay into flowers that you can bring with you.”

Sun Yue’s Field Research and Circulation of Sediment at Pearl Art Museum’s “From Clay to Words: Ceramics as Media”

From its production to its preservation, ceramic has a very strong sense of time; the theme of time permeates all ceramic works. Particularly for Sun Yue, “Ceramic conceals a layer of time or impermanence. Before it is fired, ceramic is earth and dust. Firing at more than a thousand degrees creates porcelain, hard as stone. It can last for hundreds or thousands of years, almost forgotten by time. I want to find a way to use ceramic to explore the boundaries of time and understanding from different perspectives.” Circulation of Sediment and Field Research, two of her works, are presented in the “Time” section.

Sun Yue’s Circulation of Sediment is placed in a spiral-shaped space, creating a sixty-year circular loop

Circulation of Sediment is comprised of sixty fragments of time. The Western conception of time is numerical, sequential, and irreversible, but since ancient times, the Chinese conception of time has been textual, momentary, and circular. Sun Yue spends nearly sixteen hours a day sitting at her workstation, imitating the natural geological processes of sedimentation and compression. She intersperses “sediments” of porcelain slurry and metal oxides, making sedimentary layers comprised of her own time. In this process, she captures sixty cross-sections of time that look like thin geological specimens. From the single layer of sediment on the first section, the cross-sections undergo more than a thousand layers of sedimentation and compression. The cycle ends with the sixtieth, which looks like the initial stages of sedimentation and connects to the first section. These sixty pieces are seemingly scientific, forged cross-sections of sedimentary rock, numbered in a sixty-part cycle; they are placed in a nautilus-spiral exhibition space that symbolizes time, thereby bringing viewers into the cycle of time.

Sun Yue’s Field Research at Pearl Art Museum’s “From Clay to Words: Ceramics as Media”

Sun Yue attempts to use ceramics to investigate time, as well as the cognitive boundaries of established ideas, such as perceptions of time. Field Research is a record of an outdoor comparative experiment with porcelain clay aboveground and belowground that lasted sixty-one days. Aboveground, the pieces experience sunrise, sunset, and the seasons, but underground, there is perpetual darkness and a sluggish, vague sense of time. She used Dehua porcelain (Blanc de Chine) to make ten groups of ten cones, which she placed in the unpopulated Dehua Mountains. She buried ten cones underground and placed ten cones aboveground. During the fifteen-day “culturing” period, she would observe and record a pair of the cones, one from aboveground and one from underground, every five days. Pits appeared at the top of every cone left aboveground; the pieces gradually weathered and shrunk. The underground pieces seemed to grow every day, becoming heavier. Through seemingly rational scientific study, Field Research describes and records an incomprehensible process of change related to the passage of time. This is a work that the artist made together with time and nature, blending nature and perception together in the clay.

Céleste Boursier-Mougenot’s installation Untitled Pearl at Pearl Art Museum’s “From Clay to Words: Ceramics as Media”

Liang Shaoji’s Drunkness, which involves the sense of smell, is not the only work in this exhibition to engage senses beyond the visual. Untitled Pearl is an installation that incorporates hearing and calms the soul. Created by Céleste Boursier-Mougenot, the work was completely re-designed for the exhibition space. Boursier-Mougenot studied music, and she often combines the senses of vision, touch, and hearing, using everyday implements. She creates music in her works of visual art, immersing the visitor in a multi-faceted sensory experience.

Céleste Boursier-Mougenot’s installation Untitled Pearl

In the Untitled Pearl installation, white ceramic bowls of various sizes move, touch, collide, and separate on a rippling blue pool, emitting the crisp sound unique to ceramic and evoking the ideas of cycles and eternity. Viewers can’t help but be drawn to the moving bowls and chiming tones. They sit quietly and stare, entering a mystical, peaceful state. Boursier-Mougenot said, “I have continued to make works that use physical force to create sound. In Untitled, the sounds do not simply come from the brushing or collisions of the porcelain bowls. In fact, there is a clear ‘arrangement’ of water pumps, currents, and porcelain bowls, and their movements complete the ‘composition.’ In terms of materials, I chose to use bone china bowls. These are the bowls that many people use every day; they’re very ordinary. Here, I want to say that everyday objects can become musical instruments that make beautiful sounds.”

Su Xianzhong’s Waiting for the Blooming at Pearl Art Museum’s “From Clay to Words: Ceramics as Media”

Another work that returns to simplicity and pays homage to nature is Su Xianzhong’s Waiting for the Blooming. Richly colored and differently shaped, these dense bunches of flowers are comprised of numerous little flowers, pushing the traditional “nipped flower” technique to its pinnacle and offering a new interpretation of it in the contemporary context. Making flowers is a family tradition for Su Xianzhong. Plum Blossoms, a work by his great-grandfather and famed Dehua master ceramicist Su Xuejin, won the Gold Medal at the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition. Every generation has continued to expand on the flower theme; the flowers have continued to bloom. Waiting for the Blooming is part of Su Xianzhong’s long-dormant flower series. Inspired by the 2020 pandemic, he worked from early March to late October on this pure expression of nature. Attentive viewers will discover that little birds are sitting on top of two of the clusters. As the artist has said, “It’s a reference to me.”